Drawing After the Old MastersPart 3 of 3 |

|

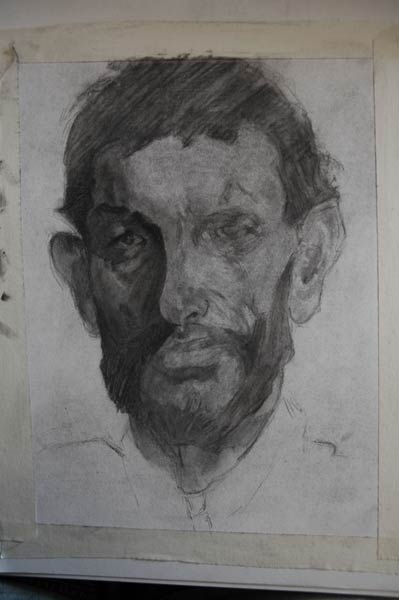

Nicolai Fechin Study

I build up the tone through several layers in order to get a range of values. In the earlier stages of developing the shading, I lay down rapid strokes with the vine charcoal in an upward diagonal pattern (easier when you’re right-handed), then I can take the brush and pull perpendicular to the stroke so that it is less pronounced, and also to push the dust further into the grain of the paper. I only brush over an area once or twice. To do so too often, would likely result in a wishy-washy study that has lost all its edges and definition. I jump from one area to another because I wish to work on the drawing as a whole, and not get lost in one particular area. EDGESThere’s not a whole lot of information covering the subject of edges, yet they can easily make or break a work of art. You may well be enhancing your drawing skills, have a good grip on shading, an understanding of form and perspective, but if you neglect your edges, your work will suffer for it. When drawing with an emphasis on line work, you can vary the width of line, or lose your contours altogether in places, getting that balance can add excitement to your work. Engaging in a painterly study, means there is less reliance on line, and more emphasis on tonal masses. The hair and beard are great examples of using edges. The dark hair stands in contrast to the background, yet a swish of the brush, pulls the dust away and creates an interesting transition; almost the impression of movement. If the whole drawing were made in this way, it may make for nauseous viewing, so you have to balance those with more solid edges, like those found in the eyes, or even subtle areas like the highlight on the nose or top of the lips. You can refer to hard edges, soft edges, broken edges, lost edges, found edges and implied edges, ultimately edges becomes an intuitive thing, and a balancing game, you need to lose enough to make the work subtle, whilst retaining enough hard edges to provide focus and solidity. When working form life, squinting often helps to show where edges are lost, and where the hardest ones can be found. When working in shadows, remember to keep your edges soft (there is little detail to be found here). Even in light areas, there is probably less detail than you imagine, and more to be found in middle tones. When making an old master study, your life is made far simpler, because the artist will undoubtedly have considered their edges carefully, and provided you with everything you need.  The background is very simple. I have no inclination to recreate those big thick impasto brushstrokes, as it is best left for oil paints. I simply take my cheap brush, dip into my container of charcoal dust, give it a couple of shakes, then push it across the paper in a very abstract and sketchy fashion. I take a look at the drawing and decide where to add a little more tone (the hair for example is unfinished), and make a few subtle alterations using my brush, putty and/or blending stump (the latter gets very little use in this study, most of the work is done with the putty and brushes), before calling it a day.

STORING / FRAMING CHARCOAL DRAWINGS The fragility of charcoal (especially vine charcoal) raises a number of questions about what you wish to do with your work. If it is a sketch or study, you may not care, and simply let nature take its course. You could try spraying it with a quality pencil/charcoal fixative. I personally try to refrain from this, as even with a few light sprays, it can affect the quality of the drawing, and the work is still at risk from smears and transfer. I tend to use acid free, PH neutral, cheap tissue paper. Cut a piece a little larger than the drawing, lay it on the top, and pop it into a rigid, inert plastic storage box. If it isn’t disturbed, then there’s no danger. If you wish to frame the work, ensure you use real glass (not the plexiglass, which can cause static and ruin your work). You can either take mountboard (aka matting), and to be safe, use two cuts to keep the drawing far away enough from the glass, or you can buy spacers, that allow you to avoid mats altogether, but again retain that safe distance that you need so that the drawing does not rub up against anything. If you want your drawing to last, you might also consider such things as using an archival masking tape, picture frames and mountboard to attach your drawing, and tape the back of the frame to prevent dust from entering. FINAL THOUGHTS There’s nothing like doing a study after an old master to make you appreciate how far your journey still lies in front of you. Given the short nature of the study, I feel I have taken away some important lessons and cannot be too harsh on my own efforts. Fechin twists and distorts features in ways that shouldn’t work, and yet they hold together with realism and expression that can’t be found from direct observation. Just look at how his ears frequently jut out, or compare an eye, or contour of the skull against something real to see how this great artist could add so much of himself to his work. It’s almost caricatured, but in subtle ways. I can’t even begin to compare, and haven’t captured that same liveliness, but just taking a little of that away with me helps in my journey as somebody self-taught, and frequently without the time to practice as often as I would like. I also have a slightly better understanding of the limitations and benefits of charcoal as a medium. Not every stroke is brushed or blended away, it has been interesting to use charcoal strokes directly, unmodified, and lay those down next to areas that have been manipulated with a finger or stroke of a brush. That painterly sort of style, that pars realism with impressionism has certainly inspired me, as I have never settled into any particular path or style, and find the likes of Nicolai Fechin a nice happy compromise between the two.

View Part TWO OF THREE Back to Part ONE OF THREE |

|

Charcoal Lessons

Charcoal |

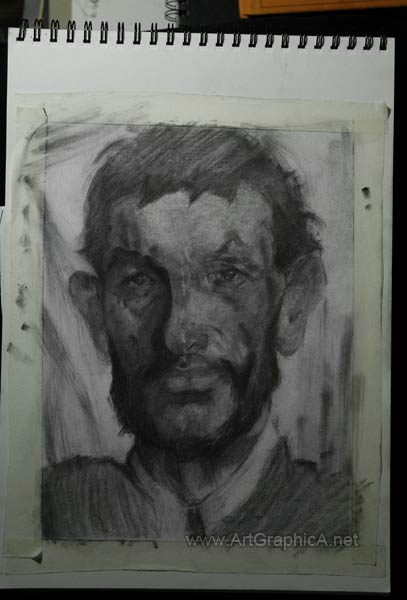

Once enough tone has been pulled off the face to distinguish light and shadow, I return to the vine charcoal and quickly redraw the features using the marks made by the general’s charcoal pencil as a guide. Fortunately the modernist black blob is slowly starting to resemble a face once more.

Once enough tone has been pulled off the face to distinguish light and shadow, I return to the vine charcoal and quickly redraw the features using the marks made by the general’s charcoal pencil as a guide. Fortunately the modernist black blob is slowly starting to resemble a face once more. The masking tape can be peeled away very simply, leaving you with an instant and gratuitous, pristine border. You can see where the dust has settled above the tape, but if you decide to frame your work, then you can hide this.

The masking tape can be peeled away very simply, leaving you with an instant and gratuitous, pristine border. You can see where the dust has settled above the tape, but if you decide to frame your work, then you can hide this.