Use of Perspective in Art |

||||||||||||||||

|

Page 21 / 25

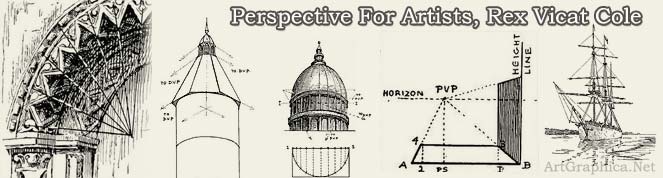

CHAPTER XX PERSPECTIVE IN SOME FRENCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGSIt would be futile to attempt a detailed description of the more modern pictures with the use their authors have made of perspective. We have spoken of Claude, and we know that Nicholas Poussin, with all his natural gifts, still made it his business to understand the principles of architecture, anatomy, and perspective, in addition to his knowledge of poetry, the classics, and mythology. Francois Millet wrote of Watteau : " The idea of marionettes always came back to my mind when I looked at his pictures, and I used to say to myself that all this little troupe would go back to their box when the spectacle was over, and lament their cruel destiny." Millet's simile of the marionettes makes me wonder if he was in particular thinking of those subjects in which small figures are scattered in woodlands, such as "Les Amusements Champetres," in the Wallace Collection. In some of these, Watteau's choice of a long-distance point gives one the feeling of figures on the stage when seen from the back of the house. In another of his pictures where there is more difference in their size they become more intimate, they are nearer to us, and we no longer feel ourselves such outsiders. Probably Watteau knew all about perspective, but I think he was careless in the comparative size of his figures in this instance, but this has no bearing on the discussion. Millet in his out-of-doors subjects was fond of placing his horizon on about the height of the chest so that the heads and shoulders of his peasants were seen against the sky, as in " Les Lavandieres " and " The Angelus." Modern French painters often set their horizon at the top of or even above their canvas, and one recalls single figures so arranged by Degas and Manet. William Hogarth with his acute knowledge of form would, as a matter of course, appreciate the possibilities for good or bad in perspective, and we see how good a use he made of it in his pictures now in the National Gallery. Don't miss the humour in his frontispiece for Kirby's Perspective (Illus. LXXV). The sign-post hung from one house with a strut supporting it from another—the " give me a light " episode, and the fisherman's float. Kirby was born in 1716 and we learn was " bred a house-painter " —he lectured on perspective by invitation of the Society of Arts in 1754, and published the " Dr. Brook Taylor's Method of Perspective Made Easy." In 1761 he published his " Perspective of Architecture." Gainsborough, as well as Hogarth, etched a print for Kirby's book, painted the portrait of him that is now in South Kensington, and directed that he should be buried in Kew churchyard, near his friend. Sir Joshua Reynolds, head of the English school, began his art education at the age of eight when he mastered the rules of " The Jesuits' Perspective," and proved them by a drawing of his father's school at Plympton (Devon). One of his notes on Du Fresnoy's poem explains concisely the purpose of perspective : " The translator has softened, if not changed the text, which boldly pronounces that perspective cannot be depended on as a certain rule. Fresnoy was not aware that he was arguing from the abuse of the Art of Perspective, the business of which is to represent objects as they appear to the eye or as they are delineated on a transparent plane placed between the spectator and the object. The rules of perspective, as well as all other rules, may be injudiciously applied ; and it must be acknowledged that a misapplication of them is but too frequently found even in the works of the most considerable artists. It is not uncommon to see a figure on the foreground represented near twice the size of another which is supposed to be removed but a few feet behind it ; this, though true according to rule, will appear monstrous. This error proceeds from placing the point of distance too near the point of sight, by which means the diminution of objects is so sudden as to appear unnatural, unless you stand so near the picture as the point of distance requires, which would be too near for the eye to comprehend the whole picture ; whereas, if the point of distance is removed so far as the spectator may be supposed to stand in order to see commodiously, and take within his view the whole, the figures behind would then suffer under no such violent diminution." No man ever carried the practice of perspective so far as J. W. M. Turner, R.A. It mattered not whether he painted the sky, the sea, the hills, or the plains, his peculiar and intimate knowledge of Nature's laws is there, combined with the theory of perspective, I have heard ignorant people doubt his knowledge of its theory ; but why ?

As a lad he worked under Thomas Malton, the topographical draughtsman who a few years before (in 1776) had written one of the largest and best works on perspective (" A Complete Treatise on Perspective in Theory and Practice on the Principles of Dr Brook Taylor "). Is it likely that Turner, who thought of nothing but his art, would miss so easy an opportunity of learning all that could be taught by that book or its author ? Neither is it likely that later in life he would have accepted the post of lecturer on perspective at the Royal Academy if he was ignorant of the science. The proof that he was not so, lies in his works. James Holland made perspective lines beautiful by filling them with great masses of light and shade. And Joseph Nash has left us a legacy in his accurate and interesting drawings of the old mansions of England. Of others, too recent to need mention, unless it were to call attention to the use Alma Tadema made of perspective in the different levels of terraces, where figures were partly hidden. In this way he gave interest to odd corners. I sometimes wonder whether the working out of the perspective itself did not suggest some of his composition. I would advise you on some slack day to make a drawing of a written description of an incident entirely by perspective rules. In doing this, first place yourself where the writer describes (or imagines) himself to have been. This fixes the horizon and D.V.P. ; this done, the objects will drop into their place automatically. The rise of the open-air school, and of the " Impressionists," is still fresh in our minds. Though the latter I believe are already old-fashioned. Theirs was an effort to record the perspective of the air, and being an honest innovation, gave impetus to the art of the day. H. H. La Thangue, I believe, was one of the first who in England put the horizon at the top of, or above, his picture. I remember one of a girl sitting by a stream, with the water continuing up the whole height of the canvas. Such an arrangement adds enormously to the attainment of realism ; provided the painter has, as in his case, the artistry to avoid the errors and unfeelingness of the snapshot photo. A painter's dream. — I should be tedious if I dragged on my notes about British artists seriatim, but the other night groups of them presented themselves to me in a dream. Will it bore you to bear it ? In my dream the painters were standing, each before a sheet of glass their perspective glasses—placed at a convenient angle, and through these they looked. Behind the glasses was Nature displaying herself in every beautiful phase. One set his glass so that he had a vista of blue lake between mountains. He painted the serene water and the perspective of the land in sunlight and shadow, and this he did so sweetly, and with reverence, that I knew him for Richard Wilson. Through another glass I saw the head and bosom of a beautiful girl. In his picture she seemed more lovable than I had at first guessed. Her face and breast where in shadow, faded into the rich red stuffs that were behind her, and these were set off with deep warm blues and creamy whites. He seemed troubled because his pencil did not catch her proportions just as they were. It mattered not that his perspective was not quite accurate, for he made her so natural and womanly that she did not even appear undressed. He signed his name Etty. A group of young men had placed themselves where there was but a small outlook. In fact a wild rose bush overhanging a little pool occupied one of them for weeks together. He copied each flower and the water, and even the fish and the stones they swam over. He knew he must paint each one beautifully, because they were all God's work and he loved them so. Later on he peeped over his glass and saw the moorlands with their moving shadows, but he could only represent with vigour their outer likeness. He marked the corner of his picture M. Another caught the dew of the morning and the glitter on the grand old elms and set them in natural groups to remind us of our country. As the wind got up he worked again furiously, so that the white clouds raced across the dark blue of his sky and the water of the mill-race flashed back its light. He seemed to be friendly with another, in more old-fashioned dress, who also painted great trees— not any particular ones—but just living things that tower above one and spread out over the pool where cattle came to drink. I could not find' out which piece he was copying, but when he had finished his labours I felt that the summer air was in them. They told me his name was Gainsborough, and he called his young friend Constable. I recognised Cotman at work because the trees seen through his glass reminded me of the dignity of architecture, and he only looked when Nature was feeling reticent. Sometimes he would walk away to the castles and copy one very faithfully, so that it looked big and grand. In this corner where the buildings were, I found pictures wonderfully life-like, but most of these were signed Sam Prout or David Roberts. The men I had seen were sitting in the front, quite close to Nature. Rows and rows of half-baked men sat behind them. These as they had no glasses of their own, looked over the shoulders of the front rank watching them work. In this way they covered their canvases, stroke by stroke, after them, so that there was some resemblance in the manner of their pictures. There were also crowds of common-looking men. Their glasses seemed to be placed so that only an ordinary, though pleasant enough view, could be seen through them. Some of these men copied their views quite nicely. I was puzzled, however, when the first man wrote A on his picture ; the next one L, and each in succession M, A, N, A, C, K. I was told the complete row formed a series which was called ALMANACK. These Calendar fellows did not trouble me much, but there were others, very ill-favoured looking men, who did not even try to trace what they could see through their misty glasses. Their hands had not the knack of forming the beautiful curves on the water surface so they represented them by straight white lines. They made but one pattern of the sky, because they continually looked at their pictures instead of through the glass. Some one told me they did these things because they had forgotten to switch on the nerve of the eye to that of the brain. To my surprise, I came across a bevy of painters reading history or anecdotes. These had put up shutters over their sheets of glass. By their side were stuffed figures oddly clothed and set in attitudes. These, and some real faces, they painted, with the surroundings that they had learnt of in books. Their paintings looked so real that I was forced to admire their intelligence, though I also perceived that without a little treatise called " Perspective " they had been unable to produce the illusion. I saw that there were many men in modern dress gazing intently through their glasses. I thought that it would have pleased my father who worshipped, and faithfully studied, the forms of nature. I was glad when a very, very old man in the front rank turned to give them a smile of encouragement. I thought, too, that someone painted a nude woman so that she had the form and dignity that belongs to Eve, and was not just a particular woman undressed. About her were children ; lovable and full of childhood, and the picture had a border of allegory, and whimsical notions thought out and drawn with consummate power. Sympathy and devotion to beauty showed in every line and stamped it as the work of Byam Shaw. Some looking through little glasses made book pictures that the people who read could know the manner of things they read of, and they were true drawings. There were so many honest craftsmen I had nearly forgotten another group. They had tilted their glasses so that the full sunlight came through them, and hovered palpitatingly over their canvas, and the group said they did it for love of Monet. Beyond the front rank men, among the golden mists of Nature herself, was a solitary figure. He was short in stature, and from pockets of his long coat there stuck out a roll of drawings. It was Turner. His brilliant and kindly eyes were taking in all Nature's secrets. They knew one another ; and she offered no resistance. For he had early won that right which others could not claim. ENGRAVINGS AND BOOK ILLUSTRATIONS The history of perspective would be incomplete without some mention of its use in books. In woodcuts of the fifteenth century, an example of the single print, " St. Christopher " (in the Spencer Library, Manchester), is a spirited design having the high horizon we commonly see in primitive work. The realistic drawing of the principal figures contrasts oddly with the bird's-eye view of the landscape. Each object tells its tale (and it does so even to the thatched roof of a house) quite independently of the matter of size or perspective of its neighbour. The British Museum contains one of the " block books "—the " Biblion Pauperum," printed about 1440. Compared with many woodcuts of a later period the perspective is none so bad though very much behind that of the best painting when we remember it was the time of the Van Eycks. The " Cologne Bible " (1475) has the usual signs of early work. Large people and rooms too small to stand up in ; here and there a piece of foreshortening seen correctly ; elsewhere receding parallel lines drawn converging, but not to the same point, and hardly ever towards the horizon. In fact an inkling of perspective but none of its science. But the heads of the figures are not so monstrously big as in the " Biblia Pauperum." In Caxton's books, such as " Game and Playe of the Chesse " and " Mirrour of the World," the drawings are very coarsely cut, but the direction of the lines on the figures is usually expressive of the foreshortening. The cuts in " Fyshynge with an Angle " (printed by Wynkyn de Worde) are very forcible though innocent of perspective. Delicate and elaborate workmanship is seen in the French and Italian prints of the fifteenth century. A woodcut from " Paris et Vienne," published. in 1495, shows the advance from the early German drawings both in the flatness of the ground the figures stand on, and some approach to correctness in the receding lines of the castle walls. The figures themselves are not correct in size one with another. A similar advance can also be noted in German cuts of the " Lubeck Bible " from the impossible perspective of say the " Hortus Sanitatis " of a few years earlier. In the sixteenth century, by the genius of Purer and Holbein and the talent of Burghmair, Aldegrever, Altdorfer, Lucas Van Leyden and others, a new epoch was opened up for engraving iu wood and copper. The exquisite work of Purer and Holbein is, I hope, a part of the education of every art student, while much can be learnt from their contemporaries ; though their perspective was not always faultless. Someone will tell me that in one of Holbein's Bible cuts —" Joab's Artifice "—the lines of the pavement, though it was intended to be level, meet at a point much below the horizon. So they do, but that does not take away from the idea of the whole scene looking correct. If beauty is appreciated and understood by an artist it is handed on by his work whether it is quite accurate or not. One could, if one wished, teach every law of nature and perspective rule, by examples of its use, misuse, or neglect in picture- books. In doing so, we should run through the history of wood- engraving from the time when beautiful work was sent out from the publishers at Lyons, and by Plantin at Antwerp. We should mention its uses in London by John Daye (" Book of Martyrs," 1562), then follow it to the end of the seventeenth century ; show how copper=plate engraving superseded it ; illustrate Hogarth and give examples of the revival under Be-wick in the eighteenth century, and of the talent later on in the engravers Linton and the brothers Dalziel. That would bring us to the artists Blake and Calvert, Rowland- son, to Dore, and presently to Sir John Gilbert, Tenniel, Birket Foster, and Leech, followed by Charles Keene. We should be nearing the end of the men who drew for the wood-engravers with Holman Hunt, Rossetti, Millais, Poynter, Sandys, and Caldecott. It would be an inadequate list, though sufficient to connect on to the introduction of mechanical process that ousted wood blocks, though fortunately leaving us artists who kept up the traditions in pen and ink. Here we should have an unlimited field for exploiting our perspective, since pictures in any medium can be reproduced. PAINTING OF SHIPS It would be interesting (but life is short) to begin a sketch of the perspective in shipping with the " red-cheeked " craft of Homeric times ; followed by the naumachim of the Roman emperors as engraved on their coins ; on till we arrived at the vessels of our forebears. There are representations of these of the time of Harold on the Bayeux tapestry, and others in the MS. illuminations of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The MS. of " Froissart's Chronicle " r illustrates the mediaeval galleys, as does also the " Chronique de S. Denis " those of the time of Richard II. The chief interest in the perspective of many of these drawings is its unexpected adaptability in showing us the ship's construction in places that should have been invisible ! A MS.[1] represents the galleys of the early fifteenth century but no sign of perspective. Henry VIII's time is depicted in the " Archmologia." Ships of a later period are seen in the illustration of the essay by Halsius Augustine Ryther, in his series of the Armada engagements, shows us galleons of the sixteenth century. We note the very common mistake of the ship being seen from one view and the sea from a higher level, a mistake by no means confined to early' work. Engravings of Dutch shipping by W. Hollar are of the middle of the seventeenth century, with Dominic Serres of the eighteenth. Not being myself a seafaring man, I asked Louis Paul (who is as crafty with a pencil as he is handy with all craft) to tell us of the perspective in the old paintings of ships. He began with a breezy account of the early sea-fights to which his opening lines here quoted refer. 1. In the British Museum. " The artistic conditions of the two centuries are as changed as the calibre of the guns, and we shall never again look upon such scenes as the old sea-fights—so let us cherish these old canvases, and look with lenient eye upon their few technical shortcomings. " The high standard of excellence in the drawing of the ships themselves is due, in some measure, to the fact that the best known of these early painters had, at some time or other in their careers, followed the sea as a profession. Richard Paton, Dominic Serres, Thomas Luny, P. J. de Loutherbourg, Brooking, Nicholas Pocock (well known by his excellent illustrations in the ' Naval Chronicle '), and of a younger generation, Van de Velde (the famous sea-scapist of the Restoration period, and esteemed as the most reliable authority of his day), these men had, each of them, ' hardened in ' the lee braces, and felt the sting of the Western ocean spray. So there is little fault to be found in poise of hull or belly of sail as painted by them. " A little lapse in Nature's laws may occasionally be discerned in their work, but we have to search diligently to find such another as Isaac Sailmaker's ' Battle of Malaga (1704),' in which that painstaking artist successfully overcomes his difficulty of representing a huge concourse of stately battleships and rakish xebecs, by elevating his point of sight a hundred feet or so, as necessary, until his horizon is sufficiently high to include all and every one of his ships—regardless of the disquieting fact that his foreground vessels must have been drawn from the water's level ! "

Next Page

Japanese Paintings Prev Page Perspective in Paintings

|

||||||||||||||||