Free Book for Learning Freehand Art

FREE-HAND DRAWING

A MANUAL FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS

BY ANSON K. CROSS

Instructor in the Massachusetts Normal Art School, and in the School of Drawing and Painting, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Author of Free-Hand Drawing, Light and Shade, and Free-Hand Perspective," and a Series of Text and Drawing Books for the Public Schools.

PREFACE

THIS book is intended for public school teachers, and for art teachers and students of elementary drawing. Its object is the presentation of artistic methods of studying free-hand drawing.

In order that this book may be inexpensive, and may meet the needs of the large number of teachers whose instruction includes outline drawing only, light and shade, which is of interest to many teachers, is made the subject of another book

An outline drawing is the most conventional of all pictorial methods of expression. It must often be incomplete, unsatisfactory, and scientific, if not mechanical. There can be but one correct representation of a cube at any given distance level and angle, and an artistic outline drawing of a geometric model is often difficult if not impossible to produce.

There are, however, artistic and inartistic ways of making an outline drawing of a cube, and if such a drawing cannot be artistic, one drawing may be less mechanical than another, and may prepare the pupil to make artistic drawings of subject which are easier to treat in this way than the exact drawing model. Many teachers think it impossible to give lessons it drawing without the use of mechanical methods, such as copying and dictating ; but in some places public school instruction is artistic. It has been shown that it is easy to start correctly in the lower grades, and not impossible for the pupils of advanced grades to change from mechanical to artistic methods.

In order that this change may be made, it is not necessary that the teachers become artists, but that they give to the subject the time required to enable them to draw simple subjects correctly.

The methods presented have been tested in elementary and advanced schools, and, if followed, will give ability to draw correctly from nature in an artistic manner.

To secure satisfactory results it is necessary that those giving the most elementary instruction understand the requirements of more advanced work. For this reason the chapter on composition has been given, and no attempt has been made to arrange the book so that teachers may study simply the directions for their special grades.

ANSON K. CROSS.

INTRODUCTION.

A DRAWING is the expression of an idea : art must come from within, and not from without. This fact has led some to assert that the study of nature is not essential to the student, and that careful training in the study of the representation of the actual appearance is mechanical and harmful. Such persons forget that all art ideas and sentiments must be based upon natural objects, and that a person who cannot represent truly what he sees will be entirely unable to express the simplest ideal conceptions so that others may appreciate them. Study of nature is, then, of the first and greatest importance to the art student.

A drawing may be made in outline, in light and shade, or in color. The value of the drawing artistically, does not depend upon the medium used, but upon the individuality of the draughtsman making it. The simplest pencil sketch may have much more merit than an elaborate colored drawing made by one who is unable to represent truly the facts of nature, or who sees, instead of the beauty and poetry, the ugliness and the imperfections of the subject.

The value depends as little upon the way the medium is used as upon the medium chosen, providing of course that the technique is not unduly prominent or offensive. Those who assert that they have found the only medium fit to be used or the only satisfactory way of handling the medium, thus prove their ignorance of the subject which they attempt to teach.

The first question for the teacher is " Shall the pupil work in color, in light and shade, or in outline ? " Color is, for the public schools at least, out of the question. Not only is it expensive, but impossible to teach. Until the students have been educated to see the actual colors of the spectrum, even the strongest artist, as teacher, would not be able to obtain satisfactory results, and for the public school teacher to attempt to teach form, light and shade, and color at first and at once is entirely beyond reason.

Choice of the drawing to be made lies between a light and shade and an outline drawing. For students outside the public schools, light and shade should be taken up as early as possible. After a few lessons in outline, a few in light and shade can be given, and the two lines of study may then be carried on together. In the public schools the study of light and shade at first or in the lower grades is unwise, and generally impossible to pursue with advantage to the pupils, for the reason that in the classroom it is almost impossible to get good light and shade upon objects placed so that they may be seen by the pupils. In the public schools the first instruction must then be in outline, and in the upper grades or the high schools, or whenever all the conditions are favorable, the study of light and shade may be begun.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

OUTLINE DRAWING

GENERAL DIRECTIONS

DRAWING FROM SINGLE OBJECTS

DRAWING FROM GROUPS

CHAPTER II.

OBJECTS FOR STUDY

CHAPTER III.

THE GLASS SLATE

CHAPTER IV. SPECIAL DIRECTIONS FOR TEACHERS.

DRAWING ON THE SLATE

FORESHORTENING

DRAWING ON PAPER

BLACKBOARD DRAWING

CHAPTER V. TESTS

CHAPTER VI. FREE-HAND PERSPECTIVE OR MODEL DRAWING

LESSON I.FORESHORTENED PLANES AND LINES

LESSON II. PARALLEL AND EQUAL LINES NOT FORESHORTENED.

VERTICAL LINES

LESSON III. THE HORIZONTAL CIRCLE

LESSON IV. PARALLEL LINES

LESSON V.PARALLEL RETREATING HORIZONTAL LINES

LESSON VI. THE SQUARE

LESSON VII. THE APPEARANCE OF EQUAL SPACES ON ANY LINE

LESSON VIII. THE TRIANGLE

LESSON IX. THE PRISM

LESSON X. THE CYLINDER

LESSON XI. THE CONE

LESSON XII. THE REGULAR HEXAGON

LESSON XIII. THE CENTRE OF THE ELLIPSE DOES NOT REPRESENT

THE CENTRE OF THE CIRCLE

LESSON XIV. CONCENTRIC CIRCLES

LESSON XV. VASE FORMS

LESSON XVI. FRAMES

DRAWINGS ILLUSTRATING THE RULES

CHAPTER VII. SCIENTIFIC PERSPECTIVE AND MODEL DRAWING

CHAPTER VIII. COMPOSITION

DEFINITIONS

FREE-HAND DRAWING.

CHAPTER I.

OUTLINE DRAWING.

AN Outline Drawing may be made in many different ways. It may be drawn with the brush, charcoal, crayon, pen and ink, or pencil. The drawing is commonly made upon paper, although it may be made on other substances. The question for the teacher is " Which is the best medium for beginners to use? " The best medium is that which requires the least thought to handle and the least time to prepare and care for ; it is that which allows the student to give all his attention to the comparison of his drawing with the object, and which admits most readily of changes. It is evident that the choice lies between charcoal and pencil, for the only value of the work is in the training and knowledge given by it. A charcoal drawing can be readily changed, but to provide this material for classes in the public schools would be very expensive, and the cause of very unclean schoolrooms. Crayon and colored chalk have no advantage over pencil : on the contrary they are more expensive, and a drawing made with them cannot be changed except with great difficulty. The pencil is not only cheaper and neater, but it requires less time to sharpen, and when rightly used the correct lines can be obtained without any erasing; so that this simple means is really the best for educational purposes.

When the crayon, red chalk, pen and ink, or the brush is used in the lower grades, the probabilities are that the aim of the instruction given is for something to exhibit, instead of for the best education.

The pencil will make a drawing with an amount of finish and effect, ranging from an outline of the simplest nature to a rendering of all the values of a complicated subject ; and when it is understood that the only worth of the drawing lies in the truthfulness with which it represents nature, we shall find childish attempts to handle difficult mediums less frequent than at present.

It is often said that there are no outlines in nature. In a way this is true, but it cannot be understood to mean that form is unnecessary or that it may be slighted. The student cannot learn to paint or to make pictures in any medium, without drawing the forms of the objects. The defining of the lights and shades and the various bits of color which are seen in nature is necessary to give solidity and character to a picture, and it is useless to think that anything can be accomplished with color or light and shade if approximate representations of form cannot be made.

Every object has definite form and size, and though it may not be outlined, it has boundaries. Although the representation of objects in outline is at best a conventional and imperfect means of expression, so far often as even form is concerned, the student can be taught to observe effects, and may often succeed in conveying a fair impression of the character of the object, and of varieties of surface and texture. He will find that the study of appearances, and their representation as fully as possible, even in so simple a way as outline drawing, will in a great measure prepare the way for work in light and shade and color. The whole question is simply one of seeing, and the student should not trouble himself over technique, as his only aim should be a true representation of nature, and it is of no consequence that such drawings by different people may be produced in different ways.

The most important points in free-hand drawing are freedom, directness, and accuracy. It is difficult to give directions which will produce these results, as individuality will prevent all from working in a uniform way. It is necessary, however, to give general directions for the work, and especially to advise the pupil not to follow the directions given in many books, written by those who are not artists or draughtsmen.

Chapter I. presents the general information required by art students and all teachers, even those of the most elementary work. Special directions are given in following chapters in order that the most important facts may be presented first.

GENERAL DIRECTIONS.

First, the surface on which the drawing is made must be held so that it is at right angles to the direction in which it is seen. If the book or paper is placed upon the desk, and the pupil looks down obliquely at it, the drawing upon it must be foreshortened so that it is impossible for the student to see what he is doing.

If the drawing is upon a block or upon paper placed upon a board, it may be held at the proper angle by the left hand. If the drawing is made in a drawing book, the book must be fastened to a stiff piece of cardboard or a thin drawing board, so that it may be properly held.

Second, the paper or book should be held as far as possible from the eyes. The student should sit back in the chair, and holding the pencil very lightly, should suggest or indicate the position of the drawing upon the paper by light lines, drawn quickly with a movement of the entire arm from the shoulder. Before beginning to draw, the student should practice this free arm movement by drawing horizontal, vertical, and oblique lines. These lines, should be drawn and redrawn, the arm passing rapidly along the paper, and the pencil point tracing line after line as near the first one as possible.

After the straight line movement, circular and elliptical movements should be practiced in the same way. These exercises should be repeated by the students whenever they have a moment not occupied, until they can sweep in an approximate ellipse, or circle, or draw a straight line with one light, quick stroke of the arm.

The pencil should be long, of medium grade, and should be held by the thumb and first two fingers, with its unsharpened end directed toward the palm of the hand. It should be held in this way for all the first work upon any drawing, but in finishing or accenting a drawing whose lines have been thus sketched, more pressure will be required, and the pencil may be held nearer the point.

If the drawing is made upon a sheet of paper, it should be secured to the board by tacks, so that its edges are parallel to those of the board ; if the edges are not quite straight, a horizontal line may be drawn near the lower edge, so that directions may be referred

to this line.

If the drawing is made in a book, the directions, vertical and horizontal, will be obtained by comparison with the edges of the book.

DRAWING FROM SINGLE OBJECTS.

We will suppose that the subject of our lesson is the box, Fig. 1.

First, nearly close the eyes and try to see the box not as a solid, but as a silhouette. The pupils will understand what is desired if an object is held in front of a window, for they will then see the object as a mass of dark, whose outlines are very distinct, while the lines within the contour are almost, if not quite, invisible. Practice will enable one to look at all objects so as to think simply of the directions of their outer lines.

To realize the directions which the important lines appear to

have, the pencil point may be moved bad( and forth in the air so that it appears to cover the edges. In other words, the lines may be drawn in the air. While doing this care should be taken to keep the pencil point where it would be if it were held upon a pane of glass placed in front of the pupil, and at right angles to the direction in which the object is seen, and not to move the pencil away from the eyes, that is, in the actual direction of the edges. This test is the most valuable of all, because it is the simplest and easiest to apply. It is really the same as the use of the thread, explained on page 47, and nearly all other means of testing will at last be discarded in favor of this first and simplest.

After careful study of the mass, its outline may be lightly sketched, no measurements of proportion having been made. The aim is to train the eye to see correctly. In order to do this, the student must depend upon his eye, and put down its first impression, rather than the results of mechanical tests of proportions. He must first draw, and then test by measuring.

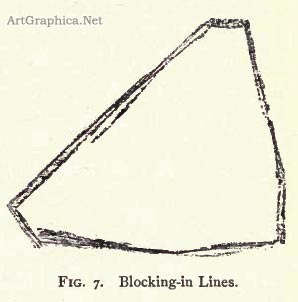

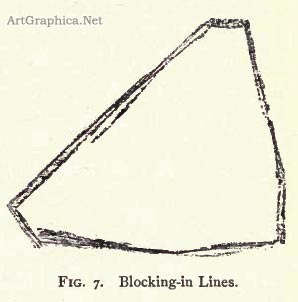

The suggesting of the mass of the drawing by light, quick lines, serves to place the drawing to the best advantage on the paper, and to introduce the draughtsman to the problem before him and to the means by which it is to be worked out. These lines are called blocking-in lines, and from such illustrations as Fig. 4, which is suggested by the cuts of a book on drawing, pupils are often led to think that a great deal of time must be spent on the lines, that they must be nicely drawn, and that every little indentation or change of form in the outline of the mass must be carefully given. Such ideas are productive of much harm. These lines should be put in lightly and freely, and should do no more than give the proportions of the drawing and its position upon the paper.

The suggesting of the mass of the drawing by light, quick lines, serves to place the drawing to the best advantage on the paper, and to introduce the draughtsman to the problem before him and to the means by which it is to be worked out. These lines are called blocking-in lines, and from such illustrations as Fig. 4, which is suggested by the cuts of a book on drawing, pupils are often led to think that a great deal of time must be spent on the lines, that they must be nicely drawn, and that every little indentation or change of form in the outline of the mass must be carefully given. Such ideas are productive of much harm. These lines should be put in lightly and freely, and should do no more than give the proportions of the drawing and its position upon the paper.

When the outline of the mass has been suggested, the inner lines may be indicated, and the result carefully studied to see that it agrees with the appearance. When no more can be done by eye alone, the drawing may be tested by measuring the proportions as explained in Chapter V. If the sketch does not agree with these tests, it must be changed. All changes should be made, not by erasing, but by drawing new lines, and the drawing should be carried on in

this way, until the correct lines are obtained.

The first lines must be very light. As changes are made, the strength may be increased to distinguish them, until the correct line is secured. The drawing having been changed to agree with the measurements of the whole height and width, and tested by moving the pencil point to cover the edges, it will be well to test it by means of vertical and horizontal lines taken through the different angles of the box. Thus, drop the pencil point vertically from point r, and see where it cuts the lower edge; carry the point horizontally from point 2, and note its intersection with the front edge. The pencil may now be made to continue the apparent directions of the edges A, B, C, etc., until the points where the continued lines appear to intersect the opposite outlines are noted. Such tests may also be applied by the pencil used as a straight edge, held horizontally, vertically, and to appear to coincide with the lines. These tests should be depended upon, and if carefully made, will produce a drawing which is practically correct. The first measurements of height and width should be very carefully taken. Distances which are nearly equal, as EF and FG, may also be compared ; but as a rule, few measurements of proportion should be made, as short distances, or short with long distances, cannot be compared with sufficient accuracy to be of any value.

Instead of the pencil the thread may be used for testing, as explained on page 47. The thread appears a fine line, whose intersections with the edges may be easily placed, so that until the eye can be depended upon, the thread is preferable to the pencil.

It is most important that all changes be made not by erasing, but by drawing new lines. Erasing and keeping but one line from first to last will generally produce a hard and inaccurate drawing ; and although it may finally be made to agree with all the tests, it will be lacking in spirit. It is difficult at first for most students to draw lightly enough to secure the correct lines without too great heaviness, but it is better, rather than to erase, to throw the drawing away and start anew, until the result can be secured without having lines so black that they cannot easily be erased.

The reason for working in this way is that we wish the student to depend, as far as possible, on his eyes. If he erases and has only one line from the start, unnecessary time is given to the drawing, and he will hesitate to change his lines. If light lines are drawn and not erased, but others drawn as soon as there is doubt about the first being rightly placed, the student is much more free to change as each suggestion occurs, and toward the last he has his choice of the various lines already drawn and can experiment freely.

This is by far the quickest and most accurate way, and prepares for rapid and truthful sketching. It is difficult at first for the student who has been taught the mechanical way of drawing one line at a time, but he will not have to draw very long in this way before he will be able to produce truthful sketches without drawing many unnecessary lines.

The student has simply to study the sketches and drawings made by the old masters, and also those by the artists and illustrators of the present day, to perceive that this is the way in which artists draw, and to see that with them, the first light touches generally remain and become part of the finished drawing.

Some artists are able to draw at first touch so as to give exact proportions to everything, but this power is due to long study resulting in thorough knowledge and ability to see correctly. This knowledge is easiest and best attained by the process of considering the subject as a whole, by suggesting all the parts at once, and then of bringing them into their proper relations as described.

In making an outline drawing pupils must erase all the first lines ; and if they are not able to obtain the correct lines without getting the paper so black that it cannot be readily cleaned, there is no reason why a hard pencil should not be used for the sketching. This outline work is simply educational, and certainly at first is not artistic. If a hard pencil is used very lightly, its marks may be removed without smooching, and the lines may be shifted a great many times without any injury to the paper. When the pupils draw more correctly, they will be able to draw the first suggestive lines with the soft pencil, which should be used in accenting the drawings.

When the correct outline has been found, it is necessary for the pupils to erase all unnecessary lines. The easiest way to do this and still retain the correct lines is to make them stronger than the others so that they will show faintly when the eraser has been passed over the paper, removing all but an indication of the desired result.

The drawing may then be accented. A soft pencil should be used, held more firmly and nearer the point. The lines should be drawn of their proper strength at one touch, and no attempt should be made to get them absolutely uniform. Much time is often wasted in such attempts, and the tendency is for too much importance to be put upon the character of the line, and too little upon the form expressed by the line. In the first work it is not necessary to think of the line, as the objects are geometric, and there is little chance for artistic effects. If the lines are put in at one touch, they will be much more satisfactory artistically than if the students are allowed to labor over them for any effect whatever.

Especially to be avoided is the smooth, even line which has the effect of having been drawn with the ruler. These lines are so inartistic that we often find labored attempts to avoid the mechanical effects due to their use. The " broad gray line," which ought from its name to be much better than the fine even line, is often more unsatisfactory, for certain valuable training results from the making of fine regular lines. No knowledge of drawing is necessary to make the " broad gray line " ; yet some seem to think this quality of line the only attribute of a good drawing, and so important that it must be obtained even at the expense of drawing two lines and carefully filling in the space between them.

The width and character of the lines are unimportant as long as they are freely draWn and express the appearance of the object.

When pupils are able to draw correctly, it will be necessary only to ask them to work as simply and directly as possible, and to make drawings which are strong and effective at a distance. To do this, they must use a soft pencil when accenting, and accent at one touch.

If the lines are put in at one touch, they will be slightly irregular and varied, and will give a satisfactory result ; for in a free-hand drawing representing even the geometric solids that have keen, sharp edges, lines which are ruled, or which are drawn free-hand to look like ruled lines, are very unsatisfactory : they produce a mechanical drawing. An artistic drawing must have variety, and must even represent sharp straight lines by lines which are not perfectly smooth and regular. This is according to the way we see these lines in Nature, for the influence of the atmosphere, which is always vibrating, causes the lines to appear not quite straight. Vibration is seen in the glittering lines of the railway track, which in summer through the hot rays of the noon-day sun seem to quiver and dance about. This and similar effects will often be seen by the student of Nature.

The pupil is frequently told to finish his drawing in lines which are strong for the parts near the eye, and lines which are light for the parts farther away. Such accenting is a mechanical application of a principle which is true and necessary in good work, but when applied without judgment to any subject, it produces the most hard and mechanical results, and students should never be allowed to accent by this or any other rule. To make an outline drawing which is artistic in its effect is a very difficult problem. It cannot be solved by the young pupil, and for the first work it is better to use lines of uniform strength and to say nothing about accenting, than it is to give a rule, or to attempt what is beyond the students' power to see and feel.

When the pupils are able to represent simple geometric forms correctly and readily, these may be arranged in groups.

DRAWING FROM GROUPS.

The student who has not had the best instruction will probably attempt to draw the objects one at a time, taking first the prism A,

Fig. 6, next the vase B, then the cylinder C, and last:the frame D.

The objection to this way of proceeding is that as the objects are drawn one at a time, until the last is completed, the proportion of the whole group-- that is, its greatest height in comparison with its greatest width --cannot be seen. Indeed, this is often not even considered, the student taking it for granted that, since he measured and tested each object as it was drawn, the single objects are correct, and therefore the group. But each object is likely to be a little out of proportion ; indeed, we may say is sure to be so. This being the case, the errors are multiplied ; and if the whole height and width are compared, the proportion is found to be far from correct.

The whole should be presented before its parts, and drawing the different objects of the group one at a time, until finally the patchwork is complete, is an uneducational way of proceeding. Practically it is also most unsatisfactory, as with each object the difficulties increase, and at7 last it be Dimes impossible to place the drawings where they belong. The only logical way is to draw the group all at once, first considering it as a mass and blocking in its proportions by lines passing from the principal points, as in Fig. 7. When these lines have been drawn and considered, they may be tested by measuring the whole height and width, and the directions tested by use of the thread or pencil ; but these lines must not follow at all closely the short lines upon the contour of the group. Their only legitimate purpose is to place the drawing properly upon the paper, and to give the extreme points of the drawing.

A good plan is, as soon as the proportions have been thus determined, to draw horizontal and vertical lines to indicate the upper, lower, right and left points of the drawing, and to be careful that the drawing is kept within these lines. The proportions of the whole group being thus determined as nearly as measurements can determine, the objects may now be sketched by eye, the most important lines being drawn first. These are the lines whose positions and directions are most easily seen. They are the longest lines, lines of one object which are nearly continuations of those of some other object, and lines which are brought out distinctly by shadow. It is evident that in this way the drawings of the different objects are proceeding at the same time, and, the shorter and less prominent lines being drawn last, the group may be said to be drawn all at once, or as if it were a single object having many parts.

While drawing, the student must think of the tests applied by the thread, of horizontal and vertical lines, and of continued lines ; and drawing in the air, by moving the pencil point to hide the edges to be represented, will also help greatly. The object should be studied in this way and changed as often as found incorrect, until the eye can do no more. It is now time to apply systematically the tests explained by the drawings of the box, Fig. 1.

The first test is to compare the height and width of each object of the group, and also to compare these dimensions with those of the whole group. This test is the most important and should be very carefully taken. Slight inaccuracy can hardly be avoided, but the longest measurements can be compared more accurately than any others, especially in the case of those which are nearly equal, and the best that can be done is to make the drawing agree with these measurements. By this time the student should be able to measure as accurately as drawings of this nature require.

These tests will generally change the drawing throughout. The changes should be made, not by erasing, but by adding lines, until without other measurements the eye can see no more to be done. The thread may then be used, first for the tests of horizontal and vertical lines, second for the continuing of all the edges, and third for covering points in the group opposite one another, that the intersections of these lines with the edges may be noted. The thread used thus will discover every discrepancy except the slight deviations which only the accurate eye can detect. The training which is given by making drawings entirely by eye and then applying tests will soon produce power to draw correctly without the use of tests.

When the correct lines have been found, the others are to be erased, as explained on page 8, and the drawing is to be accented. But now the student will do well to think of effect, and to see if more interest and expression cannot be given to the drawing than is given by uniform lines. The student has perhaps been taught that the nearest objects are seen most strongly, and that the strength diminishes with the distance. This of course is true in a general way. It is the effect of aerial perspective, or the changing of color by intervening atmosphere. Thus, of a row of light objects the nearest will appear the lightest and brightest, and of a number of dark objects the nearest will appear the darkest. The light object in the distance appears darker[1], and the dark one lighter, and in a sketch representing considerable distance this principle will be of assistance ; but it must be stated so as not to convey the idea that there can be nothing in the distance as strong or stronger than the unimportant features of the foreground, for we do not see objects more or less distinctly according to their distance, -- in fact, distance has practically nothing to do with it. We distinguish objects as masses of color, lighter or darker than the colors against which they are seen. This being so, it is evident that a light object in the background, as a white house seen against dark foliage, must be much more prominent than a near object, seen against another of the same color.

* 1. Very light objects may change but little.

In general, when there is little or no contrast of color, objects are difficult to see without regard to their distance. Place a square of white cardboard in front of a larger square of the same, the latter coming in front of the blackboard. The smaller can be seen very faintly. In comparison with the distinctness with which the larger is seen against the blackboard, the smaller is practically invisible. This experiment proves that we distinguish objects through contrasts of color, and we have to consider what can be done in mere outline to render the effect of Nature. Can no more be done than to represent the form by lines of uniform strength ?

The opinion seems to be general that more can be done. We find that instruction is often given to represent the nearer edges by strong lines, the farther ones by light lines ; in fact, to proportion the strength of the line to the distance of the part it represents. Apply this rule to the representation of the two pieces of cardboard, and the nearer is accented by heavy lines, the farther by light lines. This is a direct contradiction of what we see, for the outline of the nearer is barely visible, while the farther is distinct against the blackboard.

In color we certainly should not think of representing the nearer as darker than the farther, or in any other way than as it appears, and the same is true of light and shade. Why should we not do the same when possible, with outline ? No reason to the contrary can be given, for the difference in clearness with which the various lines are seen is the result, not of distance, but of contrasts of color, and light and shade. Of course we shall expect to find the strongest lines among the nearest ones, but farther than this we cannot go, and if we adopt any conventional accenting, we are working by rule and not by observation, and the result will be the production of hard, mechanical drawings.

Character appears in outlines. An object, as a cast, having a smooth, hard surface, shows these qualities in its outlines, which will be represented by relatively smooth lines. A cube with smooth faces has sharp, straight edges, which will be represented by straight lines. A box made of rough boards has broken edges, whose character may be given by drawing the irregular outline in which one surface breaks into the other. A drawing from the figure can express the variations in the appearance of the outline, parts of which are sharp, other parts blurred by light or a growth of hair.

Light affects the appearance of the outlines strongly, in some places making them distinct, in other places indistinct. An even line for everything disregards all these variations of effect ; so also does any conventional variation of strength. If the student is allowed to disregard effects in outline work, he will have great difficulty in seeing them in later work. There is no more labor involved in representing effects than in disregarding them, for one line is as easy to make as another, observation only being required. The student who can see, can in time represent what he sees, and as long as any differences can be found between his drawing and Nature, he can learn to correct the errors.

The conventional accenting taught in many public schools produces the most mechanical, hard, and unnatural sketches when the student works from Nature, indoors or out. Undirected he would never produce such childish and ridiculous effects, but after instruction in drawing, which has specified that lines must be represented with a degree of strength corresponding to their distance, he naturally does not think of observing and drawing what he sees, but simply mechanically grades the strength of line as he has been taught. He makes the heaviest lines of the drawing where there should be the faintest indications of lines, and often where no lines at all would be better than faint ones.

It is almost impossible to get a pupil from most public schools to make sketches in which the unimportant detail, which is no part of the effect, is not brought out with heavy black lines. This is not surprising, for he sees this detail and it is near him, therefore, according to his instruction, it must be strongly accented.

In outline, as in other mediums, we should do the best we can to express what is before us. The effect of the subject should be considered as well as its form. There is no reason why the student should not be taught to observe the effect, and if once started rightly he will advance rapidly and will make drawings which, since they are representations of Nature, will have variety of effect, will be true and artistic. No rule for accenting can be given other than to study and represent what is seen, as far as possible, as it appears.

In outline, without any light and shade, it is impossible always to accent the lines just as they appear. For instance, some edges of the object may be so lost in the shadow as to be wholly invisible, but without them the drawing might be incomplete and unsatisfactory. A correct impression of the facts must be conveyed, and no important line of a visible surface can be omitted even if not seen. Thus, in a brick or other building, when the light comes from directly behind the spectator, and the walls of the building are foreshortened equally, the front edge of the building will be invisible, unless it is brought out by different material or color. In an outline sketch of the building it would be necessary to represent this invisible edge, and it might be necessary to represent it by a very strong line, since the edge is the nearest line of the building. Thus the judgment and good sense of the draughtsman must decide what will give the best impression of the facts that the medium is capable of rendering.

In drawings of the geometric solids, where there are few lines, it will often be impossible to accent the lines as they appear ; for some of the most important ones may be invisible, or seen so faintly that to represent them as they appear would make the drawing give a false impression. Frequently when the objects are strongly lighted and arranged as in Fig. 8, their outlines on the light side of the group intersect one another, so that the outline of the mass is composed of parts of those of several objects. This outline is very prominent, while the edges inside the outline are almost lost in the mass of light. It is evident that in this case we cannot accent as we see. We must accent as we feel the group, and when accenting the lines as they are seen is unsatisfactory, we must use our judgment and make the accenting express the facts. In Fig. 8, for instance, we must show that the prism A is in front of the cube B, and that the cone C is a solid and comes in front of the back faces of the cube.

When drawing from furniture or from any subject having many lines, the effect will often be satisfactory when the lines are accented as they are seen. Here there are so many lines and so many changes in direction that the parts which are not seen may not be missed, and the student can represent more nearly what he sees. But it must be understood that it is wholly a matter of feeling for which no rule can be given, and often, in such a case as that illustrated in Fig. 10, if the lines are accented as they appear, a very false idea of the facts will be conveyed, and instead of outlining the forms of the different parts going to make up the object, the outlines of the different spaces or bits of background seen between the various parts of the object will be given.

In drawing, these spaces should be considered, and their proportions will help to prove the work; but in accenting they are unimportant. It is important to give the form and position of the different pieces forming the object, and this must be done by the accenting in heavy lines of the important features. In such accenting, the student must remember that the heaviest accent or line will strike the eye first, and should thus be given to the nearest and most important parts, as in Fig. I I.

At first most students will have difficulty in seeing any difference in the way in which the various edges appear. This is due to the fact that but a single point can be seen clearly at any one time. The eye glances rapidly over the whole of an object, observing all its parts. We are unconscious of this motion. All parts of the object are seen distinctly, and the variety of effect is not realized. All the parts will continue to give the impression of equal strength until the ability to see the whole of an object at once has been acquired. The student must practise until he can thus see before he thinks of success in any medium, for all demand equally a study of the comparative strength of detail.

It is almost impossible for students to realize effects and masses. The best assistance in this direction is given by the use of an ordinary magnifying glass of about 12" or 15" focus. If the pupil hold this as far from him as he can and still see in it the blurred forms of the group he is studying, he will see, if his eyes are focussed on the glass and not on the group, the masses of light and dark and color which form the effect, and which he must represent if his drawing is to be true. This glass is a blur-glass, because it

blurs away the detail which the pupil exaggerates so much as to spoil his drawing. If this glass is used in light and shade and in color work, it will prove the best teacher the pupil can have. In outline work, it will enable pupils to see the difference in the effect of the different lines. After using this glass for a short time, the pupils will learn to see the whole of the group at once by looking at it with the eyes out of focus, and they will not require the blur-glass

to realize the effects they ought to represent.

It is not possible to see simply, to realize effects and masses, without the blurred vision, which gives an impression of the whole subject at once. No injury to the eyes results from proper blurring of vision by a blur-glass, but if pupils try to look through it instead of at it, they injure the sight and fail to see the masses.

Although no rule for accenting can be given, the effect is found to conform to the principle that any detail which comes in either the mass of the light or that of the shadow is unimportant. Thus an edge defining a light surface against another surface also light is not prominent, and an edge separating a surface in the shadow from another shade surface is seen faintly. The important features are those which come between the light and the shadow. But from what has been said it will be realized that an outline drawing is most conventional, and that the representation of what is really seen of outline will often be most unsatisfactory. The contour of an object is absolute, and an outline will give what the eye sees ; but to express in outline artistically the pupil must learn to feel, and this cannot be expected at first. All that one can say to the student is observe the object, and do what is seen when this does not contradict the facts.

The following suggestions may aid pupils to accent satisfactorily :

- The difference in distance of the different objects or the different parts of the same object, should be expressed by varied accenting, in which the strong lines represent important lines of the subject.

- The strongest accents should represent the nearest important lines of the subject.

- The lines of the background or any unimportant detail should be represented by light lines.

- The forms of the different objects and their different parts, instead of those of the background seen behind the objects or between its different parts, must be brought out by the accenting.

The student will often, of his own accord, break away from outline pure and simple, and introduce light and shade features. This should be allowed and recommended in the public schools as soon as the pupils are able to make fairly correct outline drawings, and to see the shadows which may serve as accents. In the drawing of the geometric objects, unless the entire light and shade effects are given, it will not be easy to improve the drawing in this way ; but in the study of common objects, or flowers and foliage, and of furniture, there will be many small cast shadows which can be seen and represented by the pupils. Even in an outline drawing these cast shadows can be expressed by a thickening of the line, and the earlier the students represent all important features that they can see, the easier it will be for them to make artistic drawings. The drawings of the shoe and stool illustrate work of this nature, which is principally outline, and in which the cast shadows are given or suggested, and serve as accents.

The next step after the addition of small cast shadows is the rendering of the masses of light and dark : this introduces " Light and Shade," the subject of another book.

From National Drawing Book

|

The suggesting of the mass of the drawing by light, quick lines, serves to place the drawing to the best advantage on the paper, and to introduce the draughtsman to the problem before him and to the means by which it is to be worked out. These lines are called blocking-in lines, and from such illustrations as Fig. 4, which is suggested by the cuts of a book on drawing, pupils are often led to think that a great deal of time must be spent on the lines, that they must be nicely drawn, and that every little indentation or change of form in the outline of the mass must be carefully given. Such ideas are productive of much harm. These lines should be put in lightly and freely, and should do no more than give the proportions of the drawing and its position upon the paper.

The suggesting of the mass of the drawing by light, quick lines, serves to place the drawing to the best advantage on the paper, and to introduce the draughtsman to the problem before him and to the means by which it is to be worked out. These lines are called blocking-in lines, and from such illustrations as Fig. 4, which is suggested by the cuts of a book on drawing, pupils are often led to think that a great deal of time must be spent on the lines, that they must be nicely drawn, and that every little indentation or change of form in the outline of the mass must be carefully given. Such ideas are productive of much harm. These lines should be put in lightly and freely, and should do no more than give the proportions of the drawing and its position upon the paper.