Art Student Book

CHAPTER III.

PROPORTION.

To give the student some idea of the meaning of proportion should be the teacher's early aim, and it will entail endless teaching, for when proportion is felt, as well as measured, little more will be left to teach.

The teachers of the humanities claim that their studies give a sense of proportion in human affairs. The art teacher may also contend that the practice of drawing, rightly pursued, leads to the same end, that a child who has made a well proportioned drawing has begun to develop the sense of proportion, a step towards the building up of the good citizen, who looks at affairs with a steady eye. Exercises which otherwise might develop the sense of proportion are often smothered by rules. Students are coached assiduously in the number of times the head measures into the body, or in constructions involving middle lines, or in blocking out details in squares or triangles, while traces of the once elaborate scaffoldings of verticals and horizontals with which students used to commence a drawing may yet be found.

As Mr. Water Sickert once wrote, "There are too many props introduced to help the student, with the result that the edge of observation is somewhat blunted."

The same may be said of perspective, the formal rules of which, hastily learned by rote, tend to atrophy the powers of observation. Students sometimes seem to think that so long as receding parallels are made to vanish somewhere, all is done that need be expected of them, with the result that on looking at the drawing we see it to be merely a travesty of the forms of what has been placed before the eye.

The writer once visited a school with some students training to become teachers, to watch the drawing lesson. Some children were drawing a box placed before the class, and at the close of the lesson the students were asked to pick out the best drawing. Papers were handed in showing some knowledge of perspective rules, and there was a chorus of dissent when the writer showed the drawing he had chosen, for not a single line was in correct perspective. But it had the right proportions, it looked like the box, whereas the other drawings were too long or too high.

Of course the student can always ascertain the proportions by measurement, but the appeal to be fruitful must be mainly to the eye. The living model, whether draped or nude, affords practice in proportion readily appreciated by students, for they know people best, and are familiar with their own build and proportions.

What are known as common objects do not, to the same extent, develop in the student this. critical faculty. Most junior students calmly make extensive alterations in vases, etc., without any qualms of conscience, while, out of doors, such objects as trees make still less appeal to the sense of proportion, for they are assumed by the beginner to have no contour or shape, and are accordingly hacked and chopped about to fit them within the limits of the paper.

With junior pupils drawing a middle line as a commencement causes misproportion, the drawing almost invariably being too wide.

Sometimes bad proportions result from the anthropomorphic bias. Young students generally draw the hands and feet too small, because small hands and feet are thought to be becoming. On the other hand they make the face too large for the head because it occupies a corresponding share of their attention.

But to a great extent this neglect of proportion arises from bad method, which goes along with confused vision. The 'drawing is often begun at the top and worked downwards, the student trusting to his luck to get the whole on the paper. Hence the legs get crowded into less than their share of the space, or the feet perhaps have to be omitted.

Too often the student proceeds in a random way which positively stultifies feeling for proportion. One often sees drawings slipping off the paper, as it were, or pushed to right or left, without artistic reason for so doing.

Right methods will do much towards securing proportion. No details should be drawn at first, but a line from head to foot establishing the whole form. Every figure, every object will furnish some such line. This line once found, the proportion of the parts can proceed steadily and safely.

The preparation of "blocking out" is often strangely misunderstood by the student, who produces a mere scribble of the figure, full of badly scrawled detail, features, fingers and toes dashed in anyhow, and criticism is countered by the casual remark that the drawing is "only sketched in." Such method, or want of it, is vicious in every way. Every line from first to last should be well considered, so that at any stage the drawing may be workmanlike, in good proportion, and expressive of the model, so far as it has been taken.

Bad proportion often results from looking along the contours rather than surveying, taking in the mass of the object. An early attempt should be made to see all the figure from head to foot.

One may put it in this way, that so long as beginners are pre-occupied with detail in contour, that is, with the forms, without making the necessary preparation of noting their directions, failure to secure good proportion is inevitable.

Obviously one corrective is to draw the whole figure every time. The art teacher is familiar with the lying excuse of the student who for want of room omits the legs, that he did not intend to draw them. Such scraps of figures defeat one of the great aims of the study.

The figure prepared or indicated, the student can then concentrate on a passage that appeals specially to him, but set out from head to foot it must be, if the exercise is to be of any value as a study in proportion, or of the action of the figure.

This method gives the clue to the treatment of the vexed question of erasure. One sometimes sees a student rubbing out, or trying to do so, a large portion of a drawing at a comparatively late stage. Such alteration is mere vexation of spirit, and an acknowledgment of a bad beginning. With a studentlike and artistic commencement little or no erasure is necessary, for the proportions should be fixed by the first strokes planted upon the paper. This requires a certain firmness and patience on the part of the teacher, and a self-denial and inhibitive power not always readily at the command of the student, who comes to the study of the model with the notion that it is possible and commendable to transfer that figure bodily to the paper. For has he not seen this done in the work of the artists he most admires ?

Generally the procedure is this. The beginner commences to draw the figure in a "blocking out" of his own fashion. Horrified at the starkness of his effort, he hurriedly covers over the first lines with detail, hoping thus to secure likeness, with the result that a figure appears represented by contour lines and looking boneless and sawdust stuffed. Hence the necessity of the student learning what is at first alien from his thought, (preoccupied as he is with realizing the object or figure before him), that there is a stage which comes before drawing, namely preparation, in which the placing on the paper, the proportions, and the directions of the forms have to be studied or analysed without reference to naturalistic treatment. It may be safely said that many students leave art study without having secured the discipline and training which rigorous search after a good preparation alone can give.

To some students it is an objection that these first strokes get in the way of the drawing, have to be rubbed out, spoil the paper, etc. To this one may reply that neatness is but a minor virtue in drawing study. Cleanliness has been said to come next to godliness, but it certainly lags a long way behind.

As a matter of fact the first strokes disappear under the later work, and if rightly placed are astonishingly useful as part of the completed study. The form comes perhaps just outside or inside the first line. In the work of the genius ( ?) who draws his line and his detail all "at one go," the result is seen in knotty swollen contours, mere exaggerations of the form.

Students often use a sheet of paper upon which to rest their hands in order to avoid soiling their drawing. They thus compel themselves to draw piecemeal, stultifying their feeling for proportion, and losing the inestimable advantage of seeing the whole of their work all the time.

Many poses, especially where the figure is seated or reclining, suggest a simple pyramidal or triangular construction such as shown in FIG. i. If the sides of the triangle are right in direction, which is easily ascertained by holding the pencil against the model and comparing with the lines on the paper, then the triangle is similar to that formed by the pose, and the proportions therefore are correct. This enables the student to proceed with the drawing without hesitation and embarrassment; the mind being at rest as regards the first lines undivided attention can be given to construction and artistic expression.

As far as possible drawings should be made sight

Fig, 1--Sketches of seated or reclining figures whose proportions are easily

ascertained by assuming them contained in triangles.

Fig.2--Sketches of recumbent figures which depend for their correct foreshortening on a

horizontal receding line, which is present in the edge of the bench.

size, that is the size of a tracing on a pane of glass held before the model. Faults in proportion often occur in drawings commenced somewhat larger than sight size, for as the student works, he forgets the scale with which he started, with the result that the proportions of his extremities and details tend towards sight size, that is too small for the general proportions of the drawing.

CHAPTER IV.

TYPE FORMS.

YOUNG students, promoted to the antique or life class, are apt to shake hands with themselves on their emancipation from the thraldom of perspective and model drawing. No more cubes and cylinders, say they in effect; we shall now feast our eyes on sinuous form and subtle modelling.

They have, however, to learn that the principles of appearance are invariable, and apply equally to the representation of living form and inanimate objects.

For example, every time the face is drawn, unless its relation with the eye level be appreciated, the student is certain to have trouble. If the model's head is on a level with the student's, the drawing may pass muster, even if no attention has been paid to perspective, but if the eye be below or above, then the law of receding parallels must be observed if the features are to be intelligently represented.

Again, beginners often fail to observe the planes of the head. Especially is this so in regard to the three planes of the front and side views, with the result that the students are unable properly to place the ear, which persists in coming forward in a distressing way. (FIG. 3).

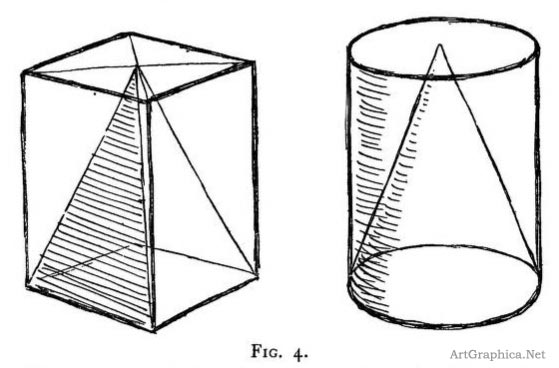

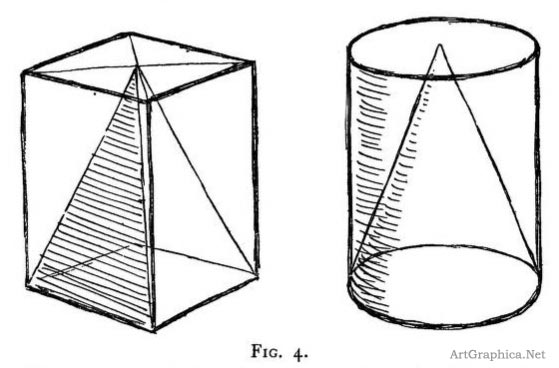

All forms, omitting the sphere, may be derived from two type forms, the square prism and cylinder. Of course by multiplying the faces of the prism one arrives eventually at the cylinder, but it will be convenient to keep them separate because each represents a different method of construction. The cone and pyramid may be ignored because as shown in FIG. 4 they are derived from the cylinder and square prism respectively.

The representation in perspective of objects based upon the square prism, depends upon the apparent convergence of parallels, which is another way of saying that things appear smaller as they are removed from the eye.

But the cylinder, though for the purposes of formal perspective considered as embedded within a square prism, and involving a somewhat intricate construction for obtaining the curve of the circle in perspective, as regards its circular end, needs not the aid of receding parallels, because when foreshortened, the circle appears as an ellipse, which should be drawn as such without any construction other than determining the direction of its long axis (always at right angles with the axis of the cylinder).

Most natural organic forms are based on the cylinder as the trunk and limbs of animals, including human beings, (though for purposes of representation these are better considered as based on the square prism), and most stems of plants and trees. Of fashioned objects, all pottery and other objects of wood or metal produced by some form of turning or lathe work, are based on the cylinder, as also tinware bent or beaten around cylindrical moulds.

Based on the square prism are framed structures as furniture and buildings, which man finds it convenient to construct with the right-angle. In the same category are building materials as bricks, cement and wrought stone, also boxes, books, etc.

FIG. 5 shows the principle of constructing the cylinder which should be followed, no matter what may be the position. It is true that some students, remembering their lessons in formal perspective, laboriously construct a prism first, but this is dreadful slavery and unnecessary, since the two straight lines forming the sides, and the two ellipses stare one in the face. Some students construct the ellipse on its long and short diameters, but these aids ruin the feeling for the curve., Sometimes the ends appear pointed owing to the fact that arcs of circles have been drawn. As a matter of fact no progress in object drawing is possible until the straight line and ellipse can be drawn freely in any position with a single movement of the hand and arm. If the student lacks this facility five minutes practice at a blackboard every day for a week at squares, circles and ellipses will set him free of these forms for life. One may observe that beginners are apt to draw the lower half of the horizontal ellipse flatter than the upper--to notice the defect is to cure it.

To the student who is content to subordinate himself to authority--and all really great artists have done this in their student days,--this constant reference to the type forms is no trammel, but a help, supplying him at once with a standard of form and a method of drawing. The head has been referred to as an approximation to the prism. The wrist is another detail of the figure which gives trouble to students. The teacher has constantly to point out the way the wrist forms a link between hand and arm, how it modifies the contour of the arm, and the 'distressing effect caused by the failure of the student to see the wrist.

The male wrist may be compared in shape- and size with a large box of matches, and this prism coming between the more cylindrical form of the forearm and the flattened form of the hand, gives this part of the arm its characteristic shape. (FIG. 6).

The male wrist may be compared in shape- and size with a large box of matches, and this prism coming between the more cylindrical form of the forearm and the flattened form of the hand, gives this part of the arm its characteristic shape. (FIG. 6).

Coming to the figure as A whole, the student must relate the great planes of the body with the faces of the prism, or fall under the penalty of failing to secure vigorous modelling.

The straight edge of the prism representing the head is replaced by the undulating line of forehead, cheek-bone, cheek and jaw, where it turns from the light (FIG. 3), and this line marks the intersection of front and side of head, two planes which present great difficulties to beginners obsessed as they are by the features. It should be borne in mind that the edge in question is a contour when seen from another point of view, and that it must relate with the contour of the further side of the head. All this applies with equal force to the trunk and limbs. The squareness of the trunk especially should be seized upon, otherwise a woolly unstructural roundness is apt to result. This intersection of the front and sides of the torse is very complicated and broken, but must be watched for. (FIG. 22).

This principle of the great planes is shown very clearly in the statues of the Egyptians. Often the limbs are absorbed so that the finished figure remains as a block. The reason, of course, lay in the material, the hardness of which prevented the sculptor from indulging in undercutting and over-modelling. (FIG. 7).

Ruskin, whose practical art teaching is always worth consideration, gave close attention to type forms. His remarks in "Modern Painters" on the construction of trees, etc., should be read carefully. His analyses of cloud forms is also very interesting and useful.

Ruskin, whose practical art teaching is always worth consideration, gave close attention to type forms. His remarks in "Modern Painters" on the construction of trees, etc., should be read carefully. His analyses of cloud forms is also very interesting and useful.

All cloud systems should be considered as horizontal. The vanishing line presents some 'difficulty, as owing to the earth's rotundity, the cloud horizon line is a little lower than that of

the earth, but the point is not of much importance.

A good exercise is a sky full of cumulus clouds, which may be likened to a number of match boxes held at a level above the eye. (FIG. 8).

The landscape painter, Boudin, should be studied for his simple systems of clouds in which the horizontality is carefully observed. An example of his work is to be seen in the National Gallery.

When clouds are approaching the eye or receding directly from it, the appearance is sometimes that of a "vertical" sky, but even in this case every effort should be made to determine the horizontal surfaces, without which the effect of distance cannot be secured.

Students often lose their grip of type forms when drawing from a pose more or less recumbent. The bench upon which the figure is lying will, if carefully observed, supply the general directions of the latter. (FIG. 2). Neglect of these simple lines accounts for many failures to secure correct fore-shortening. The same may be said of quadrupeds, as dogs and horses, drawings of which often look vague and unstable because their relation with the type prism is not sufficiently appreciated. (FIG. 9). A well-known advertisement depicts in an alpine landscape a cow much too long for its height, because the prism which forms its under-lying shape has not been properly foreshortened.

PREVIOUS PAGE

PREVIOUS PAGE

|

PREVIOUS PAGE

PREVIOUS PAGE

The male wrist may be compared in shape- and size with a large box of matches, and this prism coming between the more cylindrical form of the forearm and the flattened form of the hand, gives this part of the arm its characteristic shape. (FIG. 6).

The male wrist may be compared in shape- and size with a large box of matches, and this prism coming between the more cylindrical form of the forearm and the flattened form of the hand, gives this part of the arm its characteristic shape. (FIG. 6). Ruskin, whose practical art teaching is always worth consideration, gave close attention to type forms. His remarks in "Modern Painters" on the construction of trees, etc., should be read carefully. His analyses of cloud forms is also very interesting and useful.

Ruskin, whose practical art teaching is always worth consideration, gave close attention to type forms. His remarks in "Modern Painters" on the construction of trees, etc., should be read carefully. His analyses of cloud forms is also very interesting and useful.