Rex Vicat Cole - Free Online Art Book

The restraint and dignity of straight lines compared with a wavy outline can be appreciated even in a diagram ; there is no need for an essay ; and the strength in the rectangular limb of an Oak will be seen without having to read a disquisition. The dignity of a Lombardy Poplar is missed in the suave lines many young trees assume. The trees we call graceful and delicate are those with the curved lines ; the more subtle the curves the greater the exposition of grace. The Birch, the young Ash, the Osier and the Willow share in the charm that delicate curves can give ; but the two latter are more conspicuous for the refined lines of the stem and branches than for any definite curves in the arrangement of the foliage such as we find on Birch and Ash. Full curves, as they approach the form of a circle, have to be used with more caution than slight curves. Exaggeration in the roundness of a curve very soon gives a look of grossness, and students will remember their early difficulty of making a muscular man look muscular in their drawing and not podgy.

The outline of some trees approaches somewhat nearly to the segment of a circle. You will come across an Oak or Thorn tree of this habit ; but as a rule there is the straight line of the lower branches to steady the half circle, and this

is sometimes repeated by the line of the ground and accentuated by the perpendicular of the trunk--not a very promising form to have to tackle. Good compositions have been obtained without the expedient of

hiding the circle, but by drawing attention to it and making it the centre of other circles, the concentric character being carried out by cloud forms above, and by fallen trees, groups of figures, rock formations, lines of shadows and the like in the foreground. One would not wish to neglect the use of full vigorous curves that miss the tameness of the geometrical circle ; for they are the very embodiment of movement, life, and excitement. Wind-driven clouds with their fulness of form bellying like a sail to leeward and concave to windward teach us this ; and vigour of growth is often expressed by similar lines in foliage, and is infinitely preferable to the look of meanness assumed in a circular line pared down to gentility.

CHAPTER VI

LINES OF THE BRANCHES-CURVES-STRAIGHT LINES AND ELBOWS

INVESTIGATION of the effect of lines to be sought for among the foliage leads us to make a rough comparison of the lines we find in the branches of a tree. A somewhat detailed exposition of the branch anatomy belonging to different species is reserved for the third portion of the book ; so, in this chapter, lines will be considered generally with the view of finding out why they are interesting or dull, and what influence one has upon the appearance of another.

The full value of a line is usually obtained when it is used in conjunction with another or others. The influence of one line upon another is surprising. The straightness of one displays the curve of another. The pronounced curve of a third makes the one of slighter curve seem nearly straight, while the elbow on a fourth is so marked that it tricks one into the belief that the full curve of its companion is slight.

If lines were placed in this order, so that the fullest curve was farthest removed from the straight line (Fig. 69),

If lines were placed in this order, so that the fullest curve was farthest removed from the straight line (Fig. 69),

their difference would not attract the considerable attention that it would if they were side by side (Fig. 70) ; the degrees that lead the eye step by step would be passed without much sensation, and the fulness of the curves would be unappreciated. A similar absence of sensational effect is produced by tones of light and dark-- when black lies farthest away from white, and is joined to it by a gradation in sequence of the half-tones in the greys. Unity in the picture might be obtained by some such device in arranging lines, if that were practicable ; but it is better done by nature. Unity is gained in nature by the consistent adherence to a certain type of line in all the when black lies farthest away from white, and is joined to it by a gradation in sequence of the half-tones in the greys. Unity in the picture might be obtained by some such device in arranging lines, if that were practicable ; but it is better done by nature. Unity is gained in nature by the consistent adherence to a certain type of line in all the

ILLUS. 32 THE STEMS OF THORN TREES

ILLUS. 33. COMPARISON OF LINES-THORN STEMS

ILLUS. 34. THE TOP OF A YOUNG WHITE POPLAR - COMPARE THE ANGLES WITH THOSE OF A BLACK THORN OPPOSITE

ILLUS. 35. THE ANGLES OF A BRANCH OF BLACK THORN

individual trees of a species. On one the branches form lines that are set one with another at a small angle, on another the angle is larger. Other species exhibit slight curves, or full curves, or the boughs form elbows. One type of line is retained by each ; every branch takes its place in the scheme governed by the prevailing angle, curve, or straight line that distinguishes it, and a harmony exists that could not be if each bough and twig had a law to itself. Though every twig is formed on the plan of its neighbour, and every bough is but a twig grown old, yet endless variety is obtained by our different point of view of each. We have only to compare the foreshortened view of a branch heading towards us and that of another receding, to appreciate how inexhaustible a difference new aspects give. But boughs are not machine made--they live-- and each asserts the right to wander from the given path, or (Fig. 72) is pushed out of it by others. Age, also, rounds the angles, and robs a bough of many parts ; and the branches have that variety which belongs to a living thing, in addition to the change in appearance caused by the laws of perspective. If we wished to obtain the most startling effect, we should take the most dissimilar lines (Fig. 74) we could find and place them side by side ; they would hardly make a pleasing whole, as each be for itself and each would catch our eye separately ;  Fig. 73 --Repetition in the direction of lines Lion, but if different types are as shown in a young Oak tree Fig. 73 --Repetition in the direction of lines Lion, but if different types are as shown in a young Oak tree

We more often wish to make an assembly of lines form an agreeable whole than to use them for the display of an individual. This can be carried out in the tree by the grouping of many varied lines that conform to a definite type. The repetition of a form, whether it is beautiful or ugly, produces one sensation, but if different types are used together the result is complex and discordant.  Fig. 74.--Three types of branches on one tree

Fig. 74.--Three types of branches on one tree

ILLUS. 36 PENCIL STUDY OF THORN TREES BY R.V.C.

uncertain Hornbeam takes the dual character of Beech and Elm ; but if we look more carefully, we find here and there a loyal following of the predestined form, and this of so unmistakable a nature as to counterbalance other eccentricities. It is this recurring note that

ILLUS. 37 CHARCOAL SKETCH OF POLLARD WILLOWS

gives unity to the lines of our picture. Lines that flow in one direction only, act in unison as a single line, helping to accentuate the feeling that would be conveyed by the single line. A line full of energy might be exploited better by itself or in contrast to quiet lines ; but if the sensation of repose, quietude, and vastness can be rendered by lines of little variety, the same notion can be best insisted upon by a collection of similar lines. Those that are straight or slightly curved would, from being the least animate, form the better part of such a composition. Many groups of lines that are parallel, or nearly so, can be used in a picture ; they rm appear antagonistic only when the groups cross or are unbalanced.

For instance, the shoots on a Pollard Willow radiate in curved lines from the apex of the trunk. There is a spring in their curve that is delightful, and varied repetition adds to their charm ; remembering this, we might group the Pollards with success, when neglect of the cause of their charm would create a clashing of lines--a sort of Willow warfare that would lead to calamity.

The selection of lines is so integral a part of composition that it would be wise in spare moments to practise arrangements with any objects at hand ; ten minutes spent with a box of matches will explain the most obvious effects of one line on another (a matter to be considered daily out of doors) better than would the wading through and digesting of pages of written treatise, though the latter has the advantage of stimulating ideas. Compare A, where the matches follow the

same course but are not equally spaced, with B, where they cross anyhow ; we prefer A, but, if it is too orderly for your purpose, try a slight or greater angle of divergence, C and D. Now compare C and D with E, where the lines are equal in length. Make them quite equal and equidistant from the crossing, and they become impossible F. A literal copy of a bough is often unpleasant to look at ; the removal of one branch brings about an improvement that might lead to success if emphasis is given to certain lines and not to all equally. Branches are often so beautiful in form that they lure us on, line by line, to a detailed representation that misses the very thing we set out to draw ; it is then that we benefit by the habit of considering all objects, whether trivial or not, with a view to their artistic possibilities. The removal of one line or the placing of a stronger accent on another will often

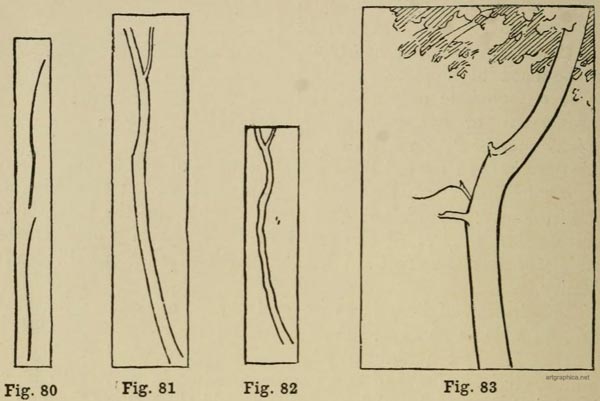

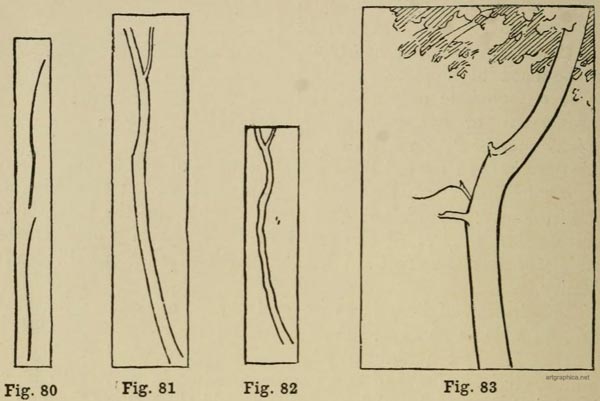

convert a faithful but poor drawing into a good one. We spoke of the contrast of curves in separate lines, but contrasts must be recognised in a single line ; call it variety if you like (Fig. 80).  A Birch stem is undeniably graceful, and the landscape man sees in it the lines that a figure painter finds in the figure of a girl ; there is the same spring and ease in the longest curve constructed of less important curves ; there are the same accents that give it strength and the same balance that brings dignity. Beginners are apt to miss the swing of the long curve by an exaggeration of the smaller (Figs. 81, 82). The lissom line, so firm and graceful, becomes degraded into a lumpy wriggle reminiscent of bent wire, or it looks flabby and unable to support the boughs and leaves that furnish it. Many stems of trees start from the ground in a perpendicular line, then break into a a short curve repeated above by a longer and A Birch stem is undeniably graceful, and the landscape man sees in it the lines that a figure painter finds in the figure of a girl ; there is the same spring and ease in the longest curve constructed of less important curves ; there are the same accents that give it strength and the same balance that brings dignity. Beginners are apt to miss the swing of the long curve by an exaggeration of the smaller (Figs. 81, 82). The lissom line, so firm and graceful, becomes degraded into a lumpy wriggle reminiscent of bent wire, or it looks flabby and unable to support the boughs and leaves that furnish it. Many stems of trees start from the ground in a perpendicular line, then break into a a short curve repeated above by a longer and

reversed one (Fig. 83). We have here the variety of a straight line and two dissimilar curves, but the accents at the junction of the curves should not be overlooked, as they influence the curves in different ways. If you draw these alternating curves as one line (Fig. 84a), it becomes a double curve without break until its meeting

ILLUS 38. THE BOUGHS OF A CRAB APPLE TREE

with the perpendicular length. If, on the other hand, you draw the alternating curves with an accent at their junction (Fig. 84b), you get two distinct curves. Again, if you miss the accent at the top of the straight length, you get much the appearance of three curves (Fig. 85) that alternate in direction. The union of one curve with another is often marked on one side of the stem by a break, while on the other side the flow of the line is uninterrupted. In place of the alternating curves we sometimes see a limb taking its course by curves facing the same direction. If this is strongly marked, a sort of kink is formed, and is of distinctive value as a relief from straight or slightly curved lines. The with the perpendicular length. If, on the other hand, you draw the alternating curves with an accent at their junction (Fig. 84b), you get two distinct curves. Again, if you miss the accent at the top of the straight length, you get much the appearance of three curves (Fig. 85) that alternate in direction. The union of one curve with another is often marked on one side of the stem by a break, while on the other side the flow of the line is uninterrupted. In place of the alternating curves we sometimes see a limb taking its course by curves facing the same direction. If this is strongly marked, a sort of kink is formed, and is of distinctive value as a relief from straight or slightly curved lines. The

individuality in the outline on either side of a bough is apparent also

ILLUS. 39. PENDENT BRANCH OF ASH

Notice the "spring" in the curves

from one outline being continuous above and below a junction (Fig. 86) and the other being broken by the added thickness of the older portion. The variety seen in curves may occasionally be due more to perspective than to any great change in their course. A young Sycamore, at times precisely symmetrical, might be irritating from the tameness of perfection if it were not for the perspective changes of the branches coming to and from us.

Our pleasure in the hanging branches is increased by the contrast of curves that spring from the upper or lower sides respectively, and in others (Fig. 87) that start from the upper side, curve downwards, and

ILLUS. 40. BRANCH OF BIRCH

Compare the loose straying of the branches with the firm lines of the Ash

then up again. Such a line as the last has all the suggestion of a steel spring and nothing of debility. We find it in the hanging branches of an

Ash. It is the same formation that in other species (Apple, Oak, Alder, Thorn, for instance) becomes a firm elbow or crozier, with less grace, but conclusive in its testimony to the strength of construction.  On these pendent boughs the curves may be repeated again and again. Truth in representation demands that our curves should conform to the habit of the tree, but a choice of curves is legitimate, even so, by painting--as if broken oft--any line we consider undesirable. We On these pendent boughs the curves may be repeated again and again. Truth in representation demands that our curves should conform to the habit of the tree, but a choice of curves is legitimate, even so, by painting--as if broken oft--any line we consider undesirable. We

are at liberty to form our curves out of the remaining portion of the parent bough, continued by the offshoot as one curve ; or we can take the parent bough and destroy the offshoot. It will he seen that the result in each case is remarkably different (Figs. 88, 89). There is a peculiar attraction in those young stems that, after some length of vertical

line, make a wriggle and continue their former course ; the halt in the undemonstrative straightness of the line piques our curiosity. It is one of the useful accidents in nature, of minor importance, that should not be forgotten in the uninspiring atmosphere of the studio ; with it rank the amusing and highly decorative loops, knots, and spirals of the clinging ivy and honeysuckle. The custom of pegging down the half- severed Ash and Beech saplings to form a hedgerow is productive of weird curves and tortuous bends, while their intermixing of roots and new-formed shoots create a fantasy out of the commonplace well worthy of consideration.

|

If lines were placed in this order, so that the fullest curve was farthest removed from the straight line (Fig. 69),

If lines were placed in this order, so that the fullest curve was farthest removed from the straight line (Fig. 69), when black lies farthest away from white, and is joined to it by a gradation in sequence of the half-tones in the greys. Unity in the picture might be obtained by some such device in arranging lines, if that were practicable ; but it is better done by nature. Unity is gained in nature by the consistent adherence to a certain type of line in all the

when black lies farthest away from white, and is joined to it by a gradation in sequence of the half-tones in the greys. Unity in the picture might be obtained by some such device in arranging lines, if that were practicable ; but it is better done by nature. Unity is gained in nature by the consistent adherence to a certain type of line in all the

A Birch stem is undeniably graceful, and the landscape man sees in it the lines that a figure painter finds in the figure of a girl ; there is the same spring and ease in the longest curve constructed of less important curves ; there are the same accents that give it strength and the same balance that brings dignity. Beginners are apt to miss the swing of the long curve by an exaggeration of the smaller (Figs. 81, 82). The lissom line, so firm and graceful, becomes degraded into a lumpy wriggle reminiscent of bent wire, or it looks flabby and unable to support the boughs and leaves that furnish it. Many stems of trees start from the ground in a perpendicular line, then break into a a short curve repeated above by a longer and

A Birch stem is undeniably graceful, and the landscape man sees in it the lines that a figure painter finds in the figure of a girl ; there is the same spring and ease in the longest curve constructed of less important curves ; there are the same accents that give it strength and the same balance that brings dignity. Beginners are apt to miss the swing of the long curve by an exaggeration of the smaller (Figs. 81, 82). The lissom line, so firm and graceful, becomes degraded into a lumpy wriggle reminiscent of bent wire, or it looks flabby and unable to support the boughs and leaves that furnish it. Many stems of trees start from the ground in a perpendicular line, then break into a a short curve repeated above by a longer and

with the perpendicular length. If, on the other hand, you draw the alternating curves with an accent at their junction (Fig. 84b), you get two distinct curves. Again, if you miss the accent at the top of the straight length, you get much the appearance of three curves (Fig. 85) that alternate in direction. The union of one curve with another is often marked on one side of the stem by a break, while on the other side the flow of the line is uninterrupted. In place of the alternating curves we sometimes see a limb taking its course by curves facing the same direction. If this is strongly marked, a sort of kink is formed, and is of distinctive value as a relief from straight or slightly curved lines. The

with the perpendicular length. If, on the other hand, you draw the alternating curves with an accent at their junction (Fig. 84b), you get two distinct curves. Again, if you miss the accent at the top of the straight length, you get much the appearance of three curves (Fig. 85) that alternate in direction. The union of one curve with another is often marked on one side of the stem by a break, while on the other side the flow of the line is uninterrupted. In place of the alternating curves we sometimes see a limb taking its course by curves facing the same direction. If this is strongly marked, a sort of kink is formed, and is of distinctive value as a relief from straight or slightly curved lines. The

On these pendent boughs the curves may be repeated again and again. Truth in representation demands that our curves should conform to the habit of the tree, but a choice of curves is legitimate, even so, by painting--as if broken oft--any line we consider undesirable. We

On these pendent boughs the curves may be repeated again and again. Truth in representation demands that our curves should conform to the habit of the tree, but a choice of curves is legitimate, even so, by painting--as if broken oft--any line we consider undesirable. We